Sonu Goswami (SaaS content writer B2B) SaaS Founders’ Playbook: Lessons from IBM Cloud Fail

Posted / Publication: Medium Sonu Goswami (SaaS content writer B2B)

Day & Date: Thursday, 2nd October 2025 Article Word Count: 2,410

Article Category: SaaS / Tech Strategy / Startup Growth

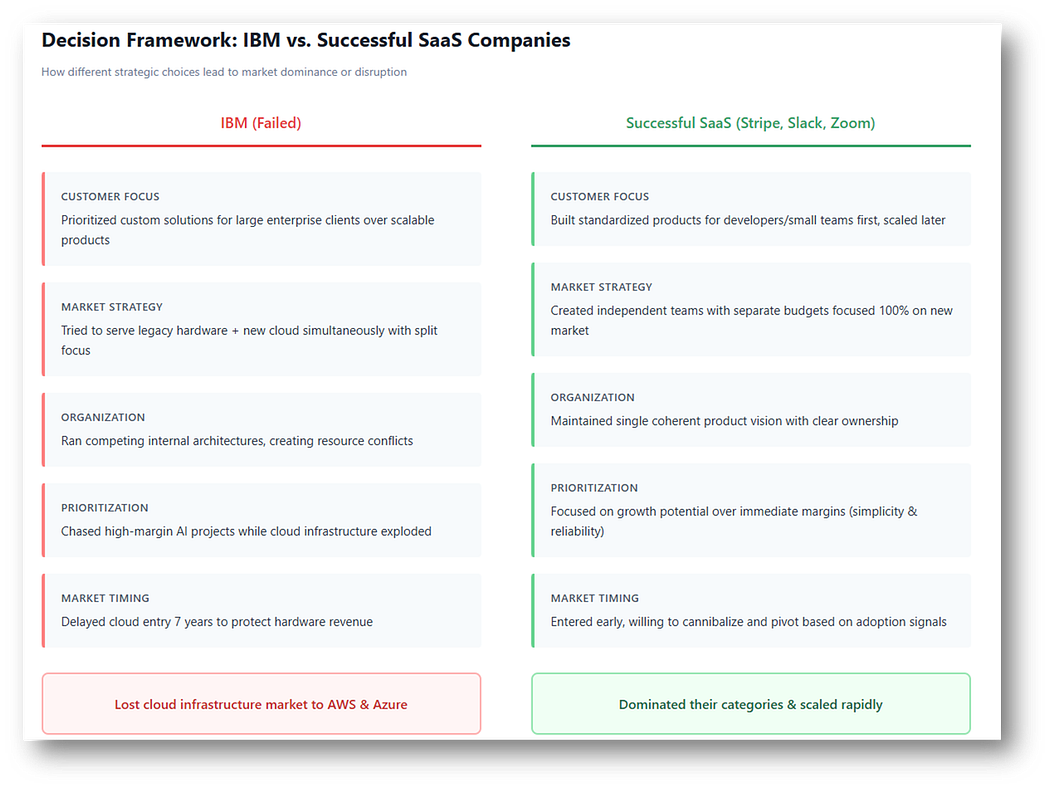

Article Excerpt / Description: Learn what SaaS founders can take away from IBM’s cloud missteps. This playbook breaks down the strategic errors, structural traps, and execution pitfalls that slowed IBM—and shows how startups can avoid the same fate. Packed with practical frameworks, real-world examples, and actionable steps, it’s all about turning insights into execution so your product doesn’t just exist—it wins.

What SaaS Founders Can Learn from IBM’s Cloud Journey: A Playbook on Avoiding Disruption

IBM’s failure to dominate cloud computing remains one of the most instructive cases in tech history. Not because they lacked foresight — they understood the trajectory early. Not because they lacked resources — few companies have ever been better positioned. They failed because organizational inertia, misaligned incentives, and poor execution consistently trumped strategic clarity.

For SaaS founders, the implications are immediate. The same dynamics that constrained IBM operate at every scale, and the window to correct course narrows quickly once momentum shifts.

The Context: Dominance Without Defensibility

By the early 2000s, IBM controlled critical infrastructure across enterprise computing:

- Enterprise hardware powering Fortune 500 data centers

- Semiconductor production for major consumer platforms

- The world’s largest enterprise software portfolio

- A consulting practice with over 500,000 active clients

Despite this positioning, AWS and Azure overtook them in cloud infrastructure within a decade. The lesson isn’t that incumbents always lose — Microsoft successfully pivoted. It’s that market position alone provides no protection against execution failures.

The parallels for SaaS are direct. Product-market fit, strong unit economics, and early traction create comfort. But they don’t insulate you from displacement if you misread how value creation is shifting.

IBM’s Early Position on Cloud

IBM identified the relevant trends by the late 1990s. They experimented with grid computing, launched Linux Virtual Services, and invested in virtualization research. The technical foundation was sound.

The problem wasn’t vision. It was the series of structural decisions that followed, each individually defensible but collectively fatal.

Seven Strategic Errors and Their Modern Equivalents

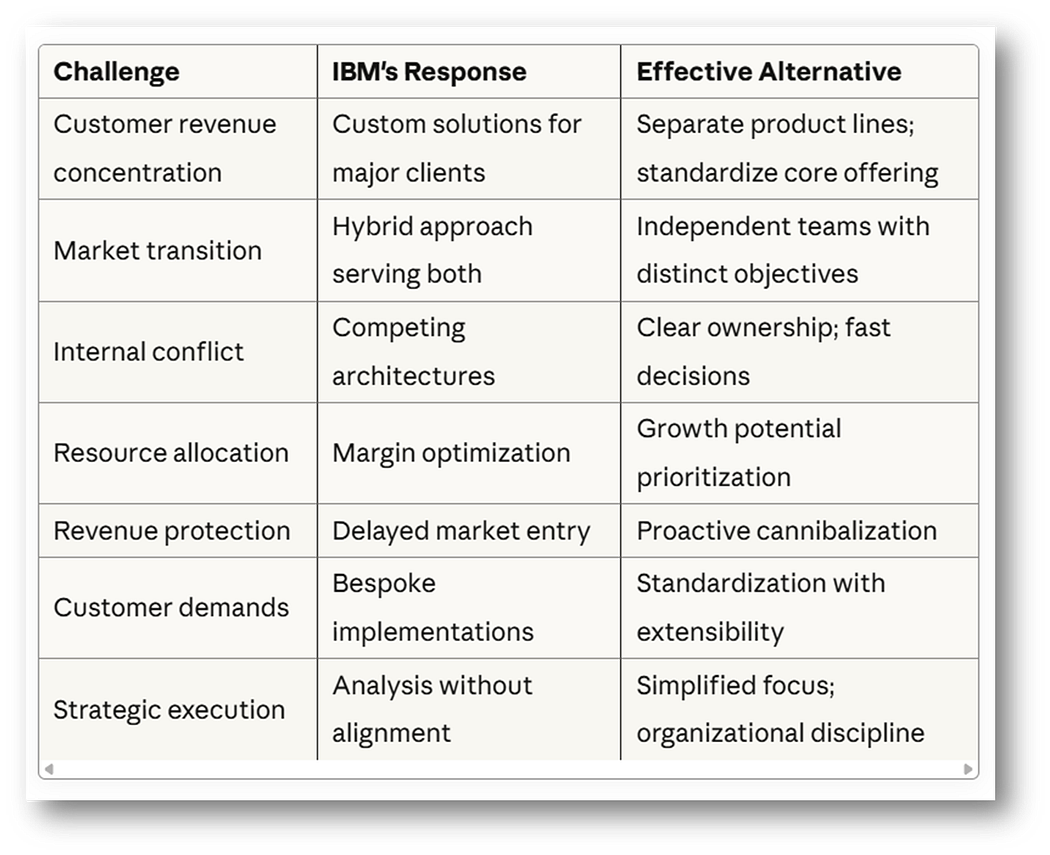

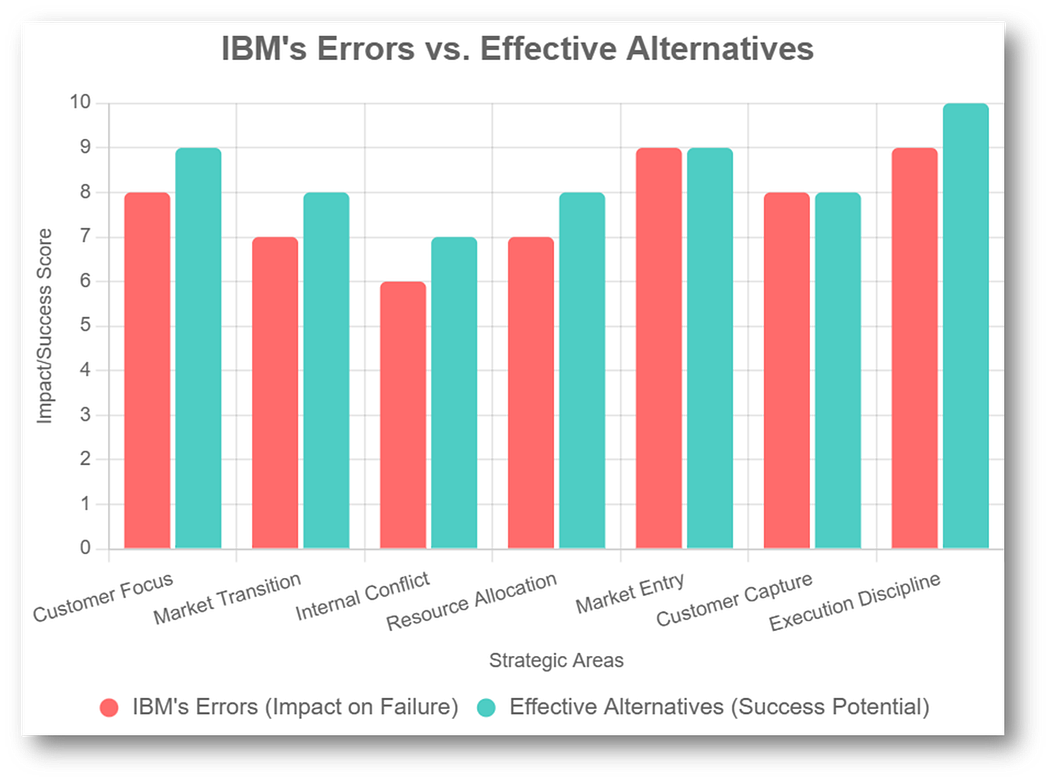

1. Optimizing for Existing Customer Revenue Over Market Expansion

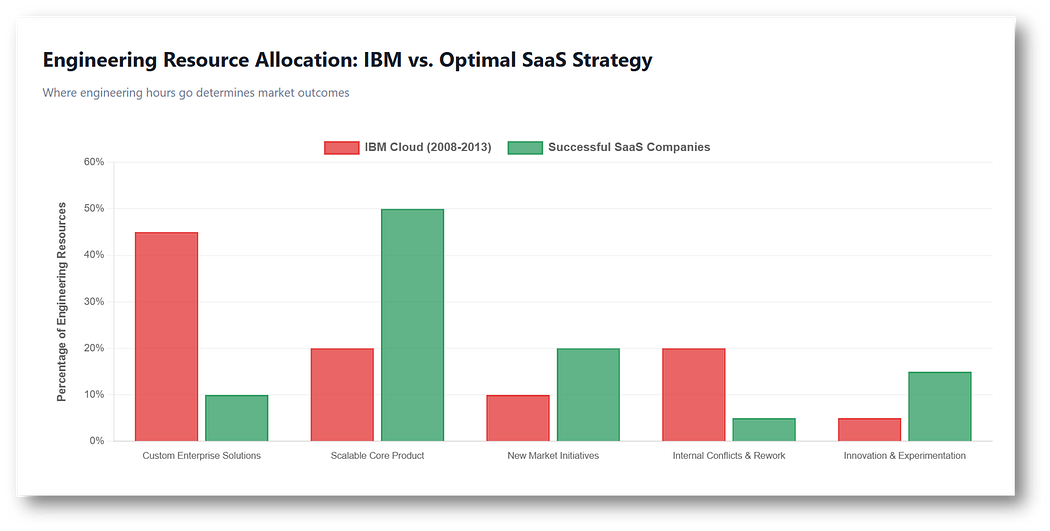

IBM’s enterprise clients generated substantial revenue but required highly customized implementations. Engineering resources concentrated on one-off solutions rather than scalable products.

The pattern in SaaS:

Enterprise deals create immediate financial validation. A handful of six-figure contracts feel more tangible than hundreds of smaller customers. But customization debt accumulates rapidly. Your roadmap becomes a negotiation with your largest clients rather than a response to market opportunity.

The correction:

Separate your core product from enterprise-specific work structurally, not just organizationally. Standardize aggressively. Use enterprise requirements to inform product direction but not dictate it. Stripe scaled by solving for developers first, then layering enterprise capabilities on top of a standardized foundation.

2. Managing Transition Rather Than Committing to It

IBM pursued a hybrid strategy, attempting to serve legacy hardware customers while building cloud products. This preserved short-term revenue but diluted focus precisely when competitors were moving with singular purpose.

The SaaS equivalent:

Maintaining complex integrations with legacy systems while building a cloud-native product. Supporting outdated pricing models while testing new ones. The intent is to smooth transition risk, but the effect is to slow execution below competitive thresholds.

What works:

Ring-fence new initiatives completely. Independent teams, separate P&Ls, distinct KPIs. The goal isn’t to manage both businesses simultaneously — it’s to prevent the old business from constraining the new one. Slack succeeded by perfecting a narrow use case before expanding, not by trying to serve multiple markets simultaneously.

3. Tolerating Internal Architectural Conflict

IBM operated two competing cloud architectures internally for years. Resources, roadmaps, and political capital were consumed by internal debates rather than market execution.

In practice:

Multiple teams building overlapping capabilities with different technical approaches. Ambiguous ownership of strategic initiatives. The organizational cost isn’t just duplicated effort — it’s the decision paralysis that prevents you from moving decisively.

The discipline required:

Clear ownership with genuine autonomy. Fast architectural decisions even when consensus is incomplete. Notion’s success came from maintaining a coherent product vision and pausing anything that conflicted with it, not from exploring every possible approach.

4. Prioritizing Margin Over Market Position

IBM invested heavily in AI and analytics during the 2010s — higher-margin work that aligned with existing capabilities. Cloud infrastructure, despite explosive growth potential, received proportionally less focus.

The founder trap:

Chasing margin-rich opportunities that leverage existing strengths feels prudent. But markets don’t care about your capabilities — they reward whoever solves the most valuable problem most effectively.

The reframe:

Evaluate initiatives by market potential and strategic positioning, not just near-term profitability. Zoom built the simplest reliable video product rather than the most feature-rich enterprise solution. When the market inflected, they were positioned correctly.

5. Delaying Market Entry to Protect Existing Revenue

IBM’s committed cloud push came in 2013, seven years after AWS launched. The delay reflected internal resistance to cannibalizing hardware and consulting revenue.

For SaaS founders:

You see a structural shift that could unlock significantly larger markets. But pursuing it means risking current revenue streams or alienating existing customers. The temptation is to optimize the current model while monitoring the new one.

The reality:

Cannibalization is inevitable. The only question is whether you control the timing. Netflix moved decisively from DVDs to streaming not because the transition was comfortable but because delaying would have meant losing the market entirely.

6. Customer Obsession That Becomes Customer Capture

IBM engineers spent years implementing bespoke solutions for major clients. This felt like strong customer service. In practice, it prevented them from building products with leverage.

The modern version:

Major clients request custom features, integrations, or implementations. Delivering these creates immediate satisfaction and retention. But each custom build increases technical debt and reduces your ability to serve the broader market.

The balance:

Customer feedback should inform product direction, not determine it. Build for the center of the market, not the edges. Shopify succeeded by creating a core platform with an ecosystem for customization, not by building custom solutions for each merchant.

7. Strategic Clarity Without Execution Discipline

IBM understood cloud computing’s trajectory. They had the right analysis. But execution — organizational alignment, resource allocation, decision speed — consistently failed.

The insight:

Strategy is necessary but not sufficient. Markets reward execution speed and focus. Microsoft’s cloud success under Nadella came from aligning culture, incentives, and execution around a clear direction, even when entering a mature market.

What this requires:

Ruthless simplification of priorities. Elimination of organizational friction. Decisiveness even with incomplete information. The goal isn’t perfect strategy — it’s rapid iteration against clear objectives.

Application Framework

Segment with precision: Separate legacy and emerging opportunities structurally. Different teams, different metrics, different decision-making processes.

Execute with speed: Reduce decision latency. Simplify organizational complexity. Ship working products over comprehensive ones.

Cannibalize proactively: Introduce new models that threaten existing revenue before competitors do. Pilot quickly, scale what works.

Standardize relentlessly: Build for the center of your market. Address edge cases through extensibility, not customization.

Monitor structural shifts: Track where value creation is moving, not just where it currently sits. Allocate resources accordingly.

Companies That Avoided These Traps

Stripe focused on developers before enterprises. Slack perfected team communication before pursuing larger organizations. Zoom prioritized reliability over features. Shopify built a platform rather than custom solutions.

None had IBM’s resources. All executed with greater focus and discipline.

Summary Framework

What SaaS Founders Should Actually Do

The IBM case study is instructive, but only if it translates into concrete operational changes. Here’s what effective implementation looks like in practice:

1. Implement a Two-Track Product Organization (Months 1–3)

The problem: You can’t serve emerging opportunities while optimizing for existing customers using the same team and roadmap.

What to do:

- Create a separate product track for new market segments with a dedicated PM and 2–3 engineers

- Give them 6-month runway with independent OKRs (not tied to current revenue metrics)

- Weekly check-ins, but no veto power from the core product team

- Budget: 15–20% of engineering resources initially

Success metric: New track ships something users can adopt within 90 days, even if minimal.

Real example: When Atlassian moved upmarket, they created a separate Cloud team that operated independently from their Server product line for 18 months before integration discussions began.

2. Establish a “No Custom Code” Rule (Immediate)

The problem: Every custom request feels strategic until you’re maintaining 40 different implementations.

What to do:

- Audit current custom work: track hours spent on client-specific code vs. core product

- Implement rule: No custom code commits without exec approval and 3-year revenue justification

- For legitimate enterprise needs, build as optional modules or feature flags accessible to all customers

- Create a “custom work tax”: any custom request requires 2x the engineering time estimate added to core product work

Success metric: Reduce custom implementation time by 60% within 6 months. Track percentage of engineering hours on scalable features vs. one-off work.

Real example: Gusto refuses custom payroll rules for individual clients. Instead, they identify patterns across requests and build generalized features that serve multiple customers.

3. Run a Cannibalization Exercise Every Quarter (Ongoing)

The problem: You won’t disrupt yourself until you’re forced to think through the scenarios explicitly.

What to do:

- Quarterly session: “If we were starting this company today, what would we build differently?”

- Identify one assumption you’re operating under that might be wrong (pricing model, target customer, core feature set)

- Run a 30-day experiment to test an alternative approach

- Budget: $5–10K and one engineer’s time for rapid prototyping

Success metric: Launch 1–2 experiments per quarter. Kill most of them. Scale the ones that show 20%+ better unit economics or 3x faster adoption.

Real example: HubSpot regularly experiments with different pricing models in isolated markets before rolling out changes. They’ve killed successful pilots when they didn’t align with long-term strategy.

4. Create Decision Speed Metrics (Month 1)

The problem: Slow decision-making feels careful but compounds into strategic paralysis.

What to do:

- Track time-to-decision for three categories: product features, resource allocation, strategic pivots

- Set targets: Feature decisions in 1 week, resource allocation in 2 weeks, strategic pivots in 1 month

- Implement “decision deadlines”: every proposal gets a decision date at intake

- Use “disagree and commit” framework: debate hard, decide fast, execute fully

Success metric: Reduce average decision time by 40% within 3 months. Track using simple spreadsheet or project management tool.

Real example: Amazon’s “two-way door” decision framework — reversible decisions get made fast by whoever owns them, irreversible ones get more scrutiny but still have tight deadlines.

5. Build a Market Intelligence System (Months 1–2)

The problem: You’re flying blind on market shifts because you’re watching metrics, not movements.

What to do:

- Assign one person to spend 5 hours/week on competitive intelligence (doesn’t need to be senior)

- Track: new entrants in your space, pricing changes by competitors, feature announcements, customer switching patterns

- Monthly report: “What changed this month that could matter in 12 months?”

- Create a “weak signals” list: early indicators your market is shifting

Success metric: Catch 3 significant market movements before they’re obvious. Make one strategic adjustment per quarter based on intelligence gathered.

Real example: Superhuman tracked every new email client launch and categorized them by approach (AI-first, privacy-focused, etc.) to identify emerging patterns before they became trends.

6. Implement a Customer Feedback Filter (Immediate)

The problem: Treating all customer feedback equally leads to building for edge cases instead of the center of your market.

What to do:

- Create a request scoring system: (Number of customers affected × Revenue potential × Strategic alignment) / Implementation cost

- Anything scoring below threshold goes to a “parking lot” reviewed quarterly

- For enterprise requests, require business case: “Would 100 customers use this, or just this one?”

- Share scoring methodology with customers so they understand prioritization

Success metric: 80% of shipped features serve 20%+ of your user base within 6 months of launch.

Real example: Linear built their entire product by focusing on requests that came from multiple customers, not individual asks. If only one company requested something, it was automatically deprioritized.

7. Run Pre-Mortems on Strategic Initiatives (Ongoing)

The problem: Post-mortems happen after you’ve wasted resources. Pre-mortems identify failure modes before you commit.

What to do:

- For any initiative over $50K or 3 months: gather team and assume the project failed catastrophically

- Spend 30 minutes listing everything that could have gone wrong

- Identify the 3 most likely failure modes

- Build mitigations into the project plan or kill the project

Success metric: Kill 30% of proposed initiatives in pre-mortem phase. The ones that proceed have 2x higher success rate.

Real example: Stripe runs pre-mortems on major product launches and regularly kills projects when the team identifies insurmountable risks, even after initial investment.

8. Create Executive Forcing Functions (Month 1)

The problem: Strategic priorities get diluted by operational noise without structural enforcement.

What to do:

- Reserve 20% of exec calendar for strategic work only (no tactical meetings allowed)

- Monthly exec session: review the 3–5 strategic bets, kill anything not showing progress

- Quarterly board meetings must include: “What did we stop doing this quarter?”

- Personal rule: CEOs should spend 50% of time on initiatives that won’t impact revenue for 12+ months

Success metric: Track how exec time is actually spent. Adjust until 30%+ is on forward-looking work.

Real example: Brian Chesky at Airbnb blocks every Monday for strategic work and product reviews. No operational meetings allowed.

Implementation Priority

If you’re resource-constrained, start with these three:

- No Custom Code Rule (Immediate impact, prevents debt accumulation)

- Decision Speed Metrics (Force multiplier for everything else)

- Two-Track Product Organization (Enables long-term optionality)

The remaining five can be phased in over 6 months as the first three stabilize.

Conclusion

IBM’s cloud failure wasn’t about missing the technology shift. They understood it early and clearly. The failure was structural: organizational complexity, misaligned incentives, and execution discipline that couldn’t match their strategic insight.

For SaaS founders, the lesson is operational, not strategic. You likely understand your market’s trajectory. The question is whether your organizational structure, resource allocation, and execution speed position you to capture it.Disruption is structural, not exceptional. What separates companies that navigate it successfully from those that don’t is execution discipline, not analytical sophistication.

The playbook is clear. Implementation determines outcomes.

I help SaaS founders by creating content that actually drives traction and growth.

FAQ – What SaaS Founders Can Learn from IBM’s Cloud Failure

1. Why did IBM fail to dominate the cloud market despite being early?

IBM understood the cloud shift, but internal structure slowed them down. The company tried to protect existing revenue streams, prioritized custom enterprise work, and made decisions slowly. Competitors like AWS and Azure moved faster with a clear focus, which allowed them to win.

2. What is the main lesson SaaS founders should take from IBM’s cloud strategy?

Early traction doesn’t guarantee long-term staying power. Even if your product is doing well, you still need to adapt quickly. The lesson is to build processes that support fast execution, not just good strategy.

3. How does serving too many enterprise custom requests create risk for SaaS companies?

Enterprise clients often request unique features, and saying yes feels like progress. But each one-off build creates “customization debt,” which makes your product harder to maintain and slows innovation. This reduces your ability to serve the broader market.

4. Why is self-cannibalization important in SaaS growth?

Sometimes the next version of your product will compete with the current one. That’s normal — and necessary. If you don’t disrupt yourself, a competitor will. Companies that avoid change because they fear losing revenue always lose market share later.

5. How can SaaS founders maintain speed as the company grows?

Keep priorities narrow, reduce approval layers, and empower product teams to ship without waiting. Fast companies aren’t fast because they work harder — they’re fast because their structure makes it easy to make decisions and execute.